He told her he knew how to do it. He told her he’d camped in the northern forest, year after year, always in mid-autumn, just him and his dog, a foxhound mix with the lungs of an Arabian stallion, who tore up and down the mountain trails, covering three or four times the distance he did, the ecstasy never once dimming in its soft brown eyes. Each time he brought along an extra sleeping bag for the dog even though the dog declined to get inside it when the nights dipped near freezing and would maybe sleep on top of it but generally preferred to curl up against him, right in the crook of his head and shoulder so that, as he tried to sleep, he heard and felt the deep breaths rumbling contentedly through the dog’s body.

He liked this part of the forest, he told her, because the shelters along the trails eliminated the need to carry a tent. The shelters were simple plank platforms with shake-shingle roofs, each with four bunk bed frames, all of it sitting on sturdy foundations built with boulders and mortar. The weathered lumber was incised and initialed, some inscriptions with dates going back forty years and some in languages from other continents.

After the dog died, he lost the will to return alone, but the memories stayed strong, the scarlet and golden mountains and forest whispers and the dog splashing through and slurping up the clear water of every brook they came across, a doggie paradise loop running endlessly in his head.

“It was paradise for you too,” she said. Continue reading

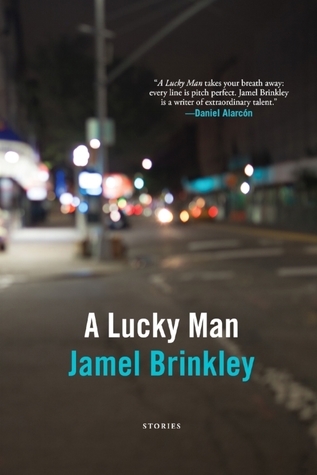

Review by E. Kirshe

Review by E. Kirshe

Recent Comments